In Which I Kind of Defend the IRS

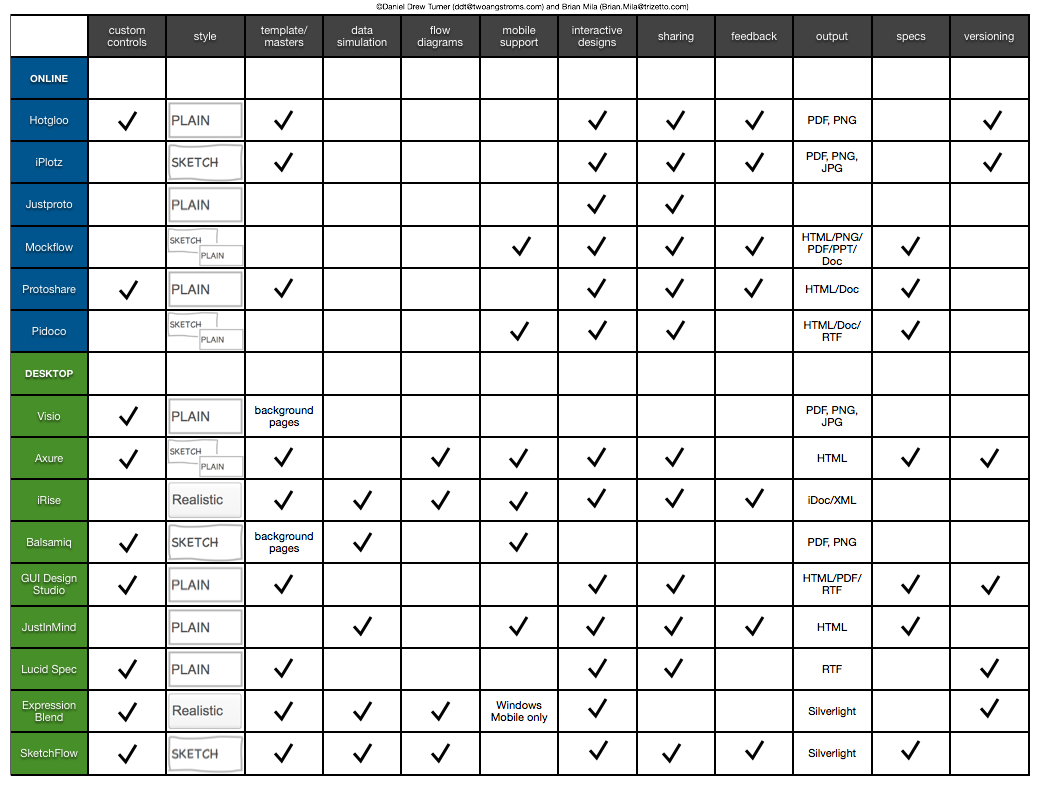

/Talking Points Memo is reporting (with a very clear chart) on the scale of the "tax gap". This gap, which unlike a "missile gap" or "shoe gap" other blind calls to blind action, seems to be real, and is defined as the delta between taxes owed and taxes paid in a fiscal year. As TPM's chart, based on numbers from the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, shows, the 2006 tax gap was $385 billion-with-a-b. This is second only to the $521 billion of military expenditures, larger than the $330 billion of Medicare spending, and a good sight more than the as-of-2006 $248 billion deficit. Neither TPM nor the CBPP go into detailed breakdowns of the gap's composition, but the CBPP was able to pick out the plurality culprit: underreporting of income. "Sole proprietors, a major class of small businesses, report less than half of their income to the IRS. In fact, under-reported business income is the single largest source of the tax gap, amounting to fully $122 billion in 2006 alone."

(This is not to pick on small businesses, the mythical all-American engine of the U.S. economy -- for dissent on that common assumption, see this NPR report. And this is not to let off the hook the "1-percenters" who move what would normally be "income" to "investment" by taking pay in stock options or other means, or place their money off-shore, or use any number of complicated dodges to end up paying low, if non-zero, tax bills. It's just that there are relatively many small business versus relatively few "fat cats", so in this case quantity of tax dodging overwhelms quality.)

It seems like a no-brainer, especially for those who spent this last summer forcing a Constitutional crisis over their avowed concern over the Federal deficit. (Or debt. They aren't always good at keeping the two straight.) These are bills that are due, bills defined and determined by tax laws agreed upon by Congress and state legislatures -- the very people who threatened a shutdown of the government over deficit issues, the very people who want to gut social programs, or kill Federal contributions to Planned Parenthood, or zero out foreign aid, as though the aggregate of those would be even a tenth of $385 billion. (Hint: they aren't. Not even close.)

A key finding in the CBPP report is this: "In the areas of the tax code with substantial information reporting and withholding requirements — most notably workers’ wages, which employers report to the IRS and on which they withhold income and payroll taxes — compliance is extremely high."

Let's go over that again. Where there are strong regulations on reporting, with enforcement, there's no problem. People report and pay their fair share, and are in the game the way it was designed, allowing other people to play fairly also. In contrast, the CBPP reports, "where there is no third-party information reporting or withholding, tax collections are abysmal."

Of course, knowing tax law, and what to report for income, can be a difficult task. No doubt reform could help some of those honestly baffled people. (Personal note: I long ago realized that paying someone to do my taxes saved me more than the equivalent in my hourly wage times the hours it'd take to understand what the hell some of these forms mean). There is generations-upon-generations of tax code, which has endured alteration and appending and what-have-you. Programmers, think of the code of a legacy application that's been worked on by hundreds of people over a decade -- spaghetti code. But the evidence shows that where there is strong regulation, there is strong compliance.

Now, how did we get here?

Just looking at the CBPP report, one can see that filling those tax code holes with strong reporting regulations would help. To quote at length:

"The Bush Administration pushed successfully for new withholding requirements on government contractors on the heels of troubling Government Accountability Office investigations showing widespread tax abuse. Then, in the 2010 health reform law, the Obama Administration teamed up with congressional Democrats to tighten reporting requirements on certain business transactions. These were two modest but real steps forward.

The current Congress, however, repealed both measures. To make matters worse, in last year’s deficit-reduction legislation (the Budget Control Act), House Republicans blocked Senate Majority Leader Reid’s effort to ensure sufficient funding for IRS tax compliance activities, even though the Congressional Budget Office concluded that it would have generated net budget savings of $30 billion over a decade."

So the first problem is resistance to clarifying and placing strong tax code. Debate amongst yourselves where the blame falls.

A second reason is that over the last decade, various administrations and political/private forces have pressed to cut support for the IRS. This is similar to how gutting the budgets of environmental and financial regulation departments at the Federal level have left giant holes for bad behavior at minimal cost. Recently, for example, we've seen the SEC have to settle slam-dunk cases, such as against Goldman Sachs, for relatively paltry sums, with no future leverage such as legal precedent, criminal convictions, and so on -- simply because the government agency in question does not have the resources to pursue prosecution or even audit for compliance.

You can see a teacup version of this in the 2006 move by the Bush administration to fire nearly half the IRS lawyers who audited tax returns on "some of the wealthiest Americans, specifically those who are subject to gift and estate taxes when they transfer parts of their fortunes to their children and others." That administration pushed hard to alter legislation to kill the estate ("death") tax, couldn't pull it off, so went after those who enforced it, or even just checked for it. Can't figure out how to rob a bank? Maybe if you could get the security staff laid off, it'd be easier.

This is still going on. Just recently the IRS reported that it's increasingly unable to do its job due to budget cuts and staffing. From the article: "Mr. Obama last year asked for the I.R.S. budget of $12.1 billion to be increased by more than $1 billion, to enable it to hire 5,100 employees. But Republicans, who oppose the health care program, succeeded in trimming the agency’s funds to $11.8 billion in the budget approved last month."

Of course, nobody likes audits, the idea of them or the practice. It is a painful process. But three things.

First: This is how we do. Though we may disagree with how the tax revenue is spent -- and that's healthy, on both sides of the political spectrum -- it is the cost of living in a civilization. And it's important to realize that tax cheating disproportionally benefits the top of the wealth scale, while taking away from those near or on the bottom. Though this could be seen as all the more incentive for the $50k/year small businessman, or waitron, to shave a little off the income reporting, my point is that we would all be better off with more consistent enforcement.

Second: These cuts don't just mean fewer audits. The affected IRS staff are also your Help Desk. Part of the reason audits are such a painful process is because we, as individual tax filers, might not have been sure of something, and had to make a good-faith effort. And we might have been wrong to some degree. But the cuts to the IRS staff don't just mean fewer evil auditors, but fewer people to answer our questions on April 14. This cuts our ability to figure out what the hell is going on in Line 48a: "Those demands have strained the I.R.S.’s ability to respond to inquiries from the public. Nearly half the taxpayers who wrote or faxed questions waited more than six weeks for a response, the report found. Taxpayers who telephoned for information found backlogs, too, the report said, as three in 10 calls went unanswered."

Third: You know, it doesn't cost that much, as a proportion of the Federal budget, to hire back these staffers. Certainly only a few million, tops. Even if they could reduce five percent of the tax gap, that'd be over $19 billion, based on 2006 numbers. That's a pretty good cost-benefit ratio, yes?

Fully funding Head Start is less than $8 billion a year. Worth it?