...and by that I'm referring to Jakob Nielsen's 1995 article on 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design, and how they still haven't become as ingrained as they should.

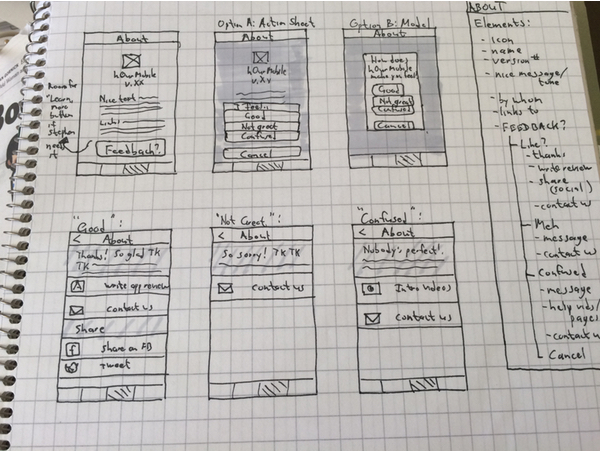

One of the things I encounter on a regular basis in my professional life is the idea that design equals "how it looks". This is not always a terrible default definition, as "design" is often about how things look (yes, of course, even color and font choices have a large effect on readability, but let's elide over that for now), but it shouldn't be the total or overwriting definition. All too often it's an uphill battle to present design as more equal to "problem solving" or "how it works". It's harder to pitch the return on investment of thinking through interaction flows than to present a pretty interface, especially to those who feel it's not something they want to spend time on.

For instance, we've had 20 years to digest and internalize the well researched precepts of what Nielsen boiled down from actual research. We do know that users find products that follow these heuristic principles easier to use and more "elegant" (we should reappropriate this term, casting it as a way to do things rather than some Apple-ish sheen), and are more likely to use and keep using said products.

Of course, some of these heuristics are harder than others to do, especially in products that gain features or are built to serve many masters. There's almost an exponential relationship between tabs or features or user goals and the work involved in making sure the product works well for the user. Nobody said it was easy to do good work.

Then again, sometimes there are examples where all it takes is open eyes and empathy for the user. As I've been known to say, "If you know how it works, you are not the user."

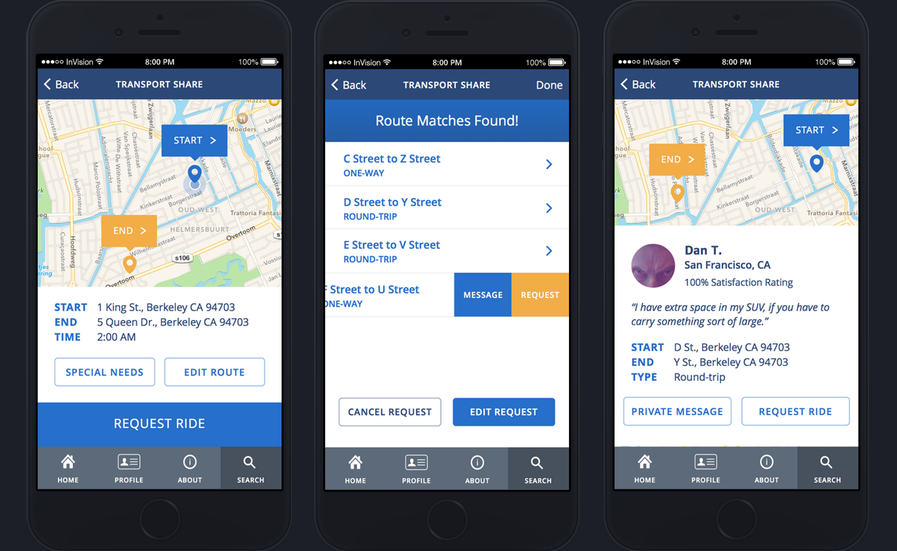

Case in point is the browser-based dashboard for Western Digital's My Cloud (and props to not making it "MyCloud"). It's fairly pretty, with nice, clear target areas to click on; this checks the "Recognition rather than recall" and "Aesthetic and minimalist design" heuristics. There's also some degree of "Consistency and standards" as well as "Match between system and the real world", if you take the real world in this case to be virtual storage spaces.

But these are the relatively easy targets, one you can hit with static sketches, with no testing in the real world. What happens when something goes wrong? Let's take, say, my case. All I wanted to do was plug in another hard drive and back it up. Given that I had most of my media on the drive, it took a while, so I left it to run overnight. The next morning, I found how to check the result (a tool tip for "Job Detail" is not great, but okay), but here's the Detail: